“House Atreides claimed to trace its roots more than twelve thousand years, back to the ancient sons of Atreus on Old Terra. Now the family embraced its long history, despite the numerous tragic and dishonorable incidents it contained. The Dukes had made an annual tradition of performing the classic tragedy Agamemnon, the most famous son of Atreus and one of the generals who had conquered Troy.”

Brian Herbert & Kevin J. Anderson, Prelude to Dune: House Atreides (pg. 21)

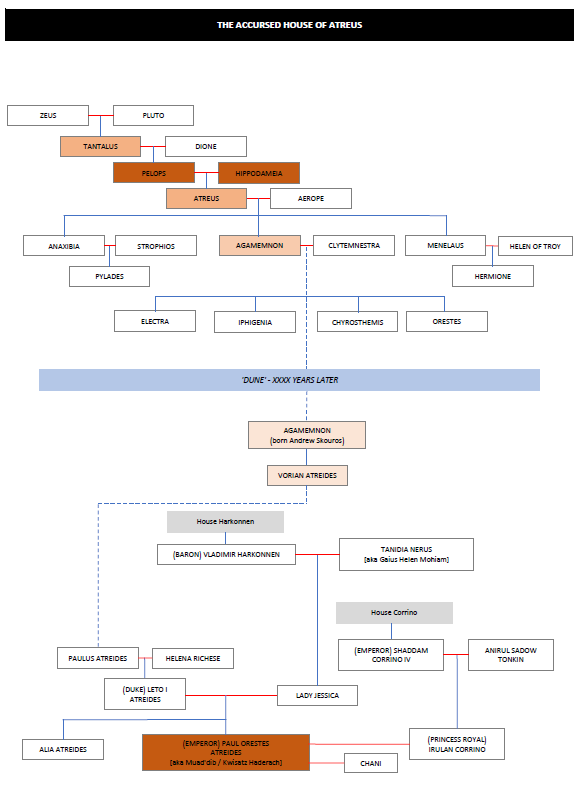

Penned by Frank Herbert, the extraordinary novel Dune and its many sequels and prequels (now totaling some 18 books) placed ancient Greek mythology at its very heart. Son of Duke Leto and the Lady Jessica, Paul Orestes Atreides, the hero of the first novel, could proudly trace his bloodline back some 12 millennia to archaic, mythological Greece.

House Atreides, which rose to prominence through the Butlerian Jihad and into the saga’s contemporary era of the Galactic Padishah Empire, dominates the books of Herbert, his son and co-author to emerge just like the ancient heroes and rulers of Greece it is claimed they derived from – the willful, often ill-fated members of the semi-divine House of Atreus.

This association with ancient Greece and ancient Greek mythology is often touched upon by commentators exploring the world of Dune and its derivatives, but few dig more deeply. This brief blog and the accompanying genealogical tree will attempt a little more excavation, as readers familiar with Dune may be pleasantly surprised to find that the central myth explored within Olympia: The Birth of the Games – that of the great generational struggle between Tantalus and Pelops – actually forms the core tale from which the world’s best-selling science fiction novel has been generated. In fact, it might be claimed that our Olympia is not only the most extensive historical fiction examination of the Tantalus-Pelops myth currently in print, but this selfsame tale that birthed the great curse of the House of Atreus underscores many of the most potent subsequent Greek myths and legends while also stretching as far forward as the heroes, anti-heroes and doomed characters of the Dune cosmology.

Our Olympic hero Pelops, son of the semi-divine Tantalus, and our heroine Hippodamia would birth a son, Atreus, to whom their family (or ‘House’) would thereafter be named. The immediate sons of Atreus, the much-famed Agamemnon and Menelaus, in their pursuit of the abducted beauty Helen, would then launch their thousand ships and 10-year campaign against the ‘oriental’ power of Troy. Not only did this ‘myth cycle’ form the heart of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey and underscore much of Classical Age Greek dramaturgy (with Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides all making significant contributions), but the great siege and subsequent sack of Troy has continued to play a central role in the Western imagination. From remarkable works of the medical imagination like Achilles in Vietnam: Combat Trauma and the Undoing of Character by Dr. Jonathan Shay to movies like Troy, where Brad Pitt and Eric Bana remind us of the bloodthirsty tragedy of archaic warfare, and into countless television series’, theatrical productions, spin-off written works, archaeological discoveries (Heinrich Schliemann’s romantically-inspired uncovering of the reputed city of Troy being just one such) and works of art, the accursed line of Tantalus still dominates our story-telling.

Arguably, where our Olympia most fully intersects with Dune is the fabled curse that was laid upon Tantalus for his horrifying crimes against his son Pelops. In the original Greek myth (or permutations thereof), Tantalus committed infanticide and a form of cannibalistic sacrilege by trying to serve up cooked portions of his murdered son Pelops to a feast he organised for the gods of Mount Olympus. In our re-telling of this myth, Tantalus attempts to poison and thereby murder his son over a meal, but ends up only slaying Oenomaus, his murderous accomplice, and insulting the gods with his fraudulent masquerading as Zeus. In any event, the great curse that was laid upon Tantalus by Zeus for his sins reverberated down through both the family line – with his grandson, Atreus, committing near-identical crimes – and across great spans of time, with Dune capturing this endless echo of doom hedging around House Atreides: Duke Leto (unable to be saved, despite his children’s formidable powers), his messianic son Paul (later blinded, like Oedipus or Homer), preternaturally gifted but stunted daughter Alia and the continuation of their line often suffered terrible fates (particularly Paul’s son, another galactic emperor, whose navigation of his awesome powers saw him transformed into something barely human) in the tradition of Tantalus-Pelops-Atreus. Truly, the divine curse laid upon Tantalus, whereby he was doomed to be tortured in Hades – or ‘tantalised’, whence the origin of the English word – for all time, endlessly stained his bloodline.

While there are many other signifiers and emblematic reminders of this shadow of Mount Olympus looming over Dune – with just a few including Duke Leto being named after the consort of the god Apollo, the family crest of House Atreides being the hawk of Apollo [see the image at the top of the blog], the dreadnought sandworms of Arrakis resembling the feared Python Apollo slew to establish Delphi and the Pythia priesthood (with the latter, in turn, reflected in the mystical Bene Gesserit) – it is the fate of the House of Atreus embedded in the sci-fi myth-making of Dune that highlights the often-tragic universality of human nature, past and present.

Heya exceptional blog! Does running a blog such as this require

a massive amount work? I have absolutely no knowledge

of computer programming however I was hoping to start my own blog in the

near future. Anyhow, if you have any ideas or tips for new

blog owners please share. I know this is off subject nevertheless I simply had to ask.

Kudos!

Hey I am so thrilled I found your site, I really found

you by error, while I was browsing on Digg for something else, Nonetheless I am here now and would just like to say thanks for a marvelous

post and a all round exciting blog (I also love the theme/design), I don’t have time

to go through it all at the moment but I have bookmarked it and also added your RSS feeds, so when I have time

I will be back to read a lot more, Please do keep up

the fantastic b.

Hello, I enjoy reading through your article post. I like to write

a little comment to support you.

This is my first time pay a visit at here and i am

in fact impressed to read all at one place.

Greetings from Florida! I’m bored at work so I decided to check out your website on my iphone during lunch break.

I really like the knowledge you provide here

and can’t wait to take a look when I get home.

I’m amazed at how quick your blog loaded on my mobile ..

I’m not even using WIFI, just 3G .. Anyways, fantastic site!

Very quickly this website will be famous amid all blog users, due to it’s nice articles

Outstanding post but I was wanting to know if

you could write a litte more on this subject? I’d be

very grateful if you could elaborate a little bit more.

Kudos!

My spouse and I absolutely love your blog and find a lot of

your post’s to be precisely what I’m looking for. Do you offer guest writers to write content for yourself?

I wouldn’t mind producing a post or elaborating on many of the subjects you write related

to here. Again, awesome blog!