Book Review: ‘Olympia: The Birth of the Games’: A Fun, Though Violent Perspective of the Start of the Olympics

BY DUSTIN BASS TIME AUGUST 22, 2022

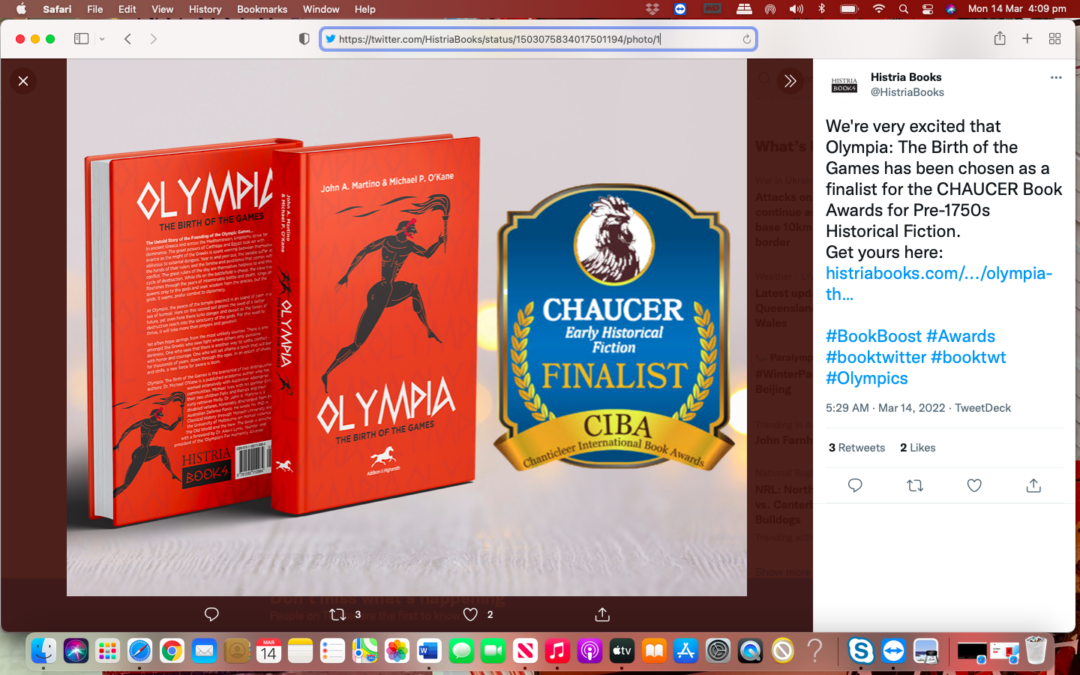

What is the true story of how the Olympic Games began? John A. Martino and Michael P. O’Kane, authors of “Olympia: The Birth of the Games,” have endeavored to tell that story in their new novel. This historical fiction account takes the reader back to the year 776 B.C., in the Greek city of Olympia.

The story, however, doesn’t revolve around Olympia. Rather, it revolves around the region as the reader follows the exhilarating and often bloody adventures of Pelops, the son of the priest of Olympia. Pelops is a man of peace in a world of continual wars. The authors express a cycle of violence that no one believes can be—and most don’t want to be—stopped.

“Olympia” is a fun read with interesting characters who are colorful in various ways, whether they be kind, vicious, humorous, serious, redemptive, or unredeemable. The pacing of the read is hardly slow. There is constant action of some kind, starting with a battle scene, moving to a suicidal rescue mission, and ending with the high pressure of competing in the first Olympic Games (which prove more violent than what is known in the modern games).

From a historical perspective, the players, time, and location are familiar and accurate, though the players are often enshrined in mythology. The temperament of the political and military leaders is often unforgiving and ruthless. Taking into consideration how leaders of Greek city-states treated their enemies, and at times their own people, those attributes aren’t too implausible (though at times they do feel over-the-top).

The authors demonstrate through these leaders a continual struggle for supremacy, through either deception or warfare. Perhaps one of the goals of the book is to suggest a replacement for warfare: games.

An Underlying Meaning

“Olympia” tends to do more than try to tell the story of the origin of the Olympic Games. The book also looks to be an antiwar historical fiction novel, not that that isn’t a noble aim. Through Pelops, and a few other good-hearted characters in the book, the purpose of the games is to unify the Greek city-states and bring the known world together through nonmilitary means.

The competition held in Olympia, in the western part of the Peloponnese, in 776 B.C. was a moment for citizens of various countries like Carthage, Sparta, Nubia, and others to demonstrate their strengths and talents against each other.

In the story, the effort for unification, eliminating bad alliances, and bringing about peace is somewhat successful. I say “somewhat” because the story ends before those elements are fully known. But historically, after the games, wars and strife continued.

The games, even now, do present a unifying spectacle that offers citizens of the world a glimpse of how similar we all are, despite our nationalities and cultures, through sportsmanship. This has been shown time and again, even during conflict.

Since the introduction of the modern Olympic Games in 1896, competitors from different countries have shown that they are able to put their differences aside to encourage, assist, and congratulate each other.

Fun With a Few Flaws

As mentioned earlier, “Olympia” is a fast-paced book with plenty of action and suspenseful scenarios. There is no shortage of heroes and villains, and the story allows those characters to face off in a singular event. And it doesn’t always go the way the reader might expect, which is a pleasant surprise. The authors show that they aren’t afraid to sacrifice some of their characters to keep the reader engaged.

The authors rely heavily on dialogue, which can be hit-or-miss. They utilize swears or oaths for their characters, like “Who in Hades is this?” and “Oh, gods!” which feels rather contrived. The authors also use the ellipsis for dramatic effect at an almost haphazard level.

There were a few confusing parts at the end. At one point, all the royalty from the other nations and city-states left in anger before the games ended, but then were seated to watch the final event. The father of the protagonist takes his vengeance out on someone who poisoned his son, but the authors make it clear (at least, it was clear to this reader) that the father knew of the poisoning before it took place. And as mentioned before, sometimes the dialogue is hit-or-miss and descriptions of the characters’ temperament (predominantly the villains) are over-the-top.

For readers with an affinity for ancient Greek stories and myths, “Olympia” should prove to be a fun read.

(Text reproduced with permission)